Android Origins

On the French king's doctor, Monsieur Le Cat, Czech theatre, and the roots of "robot" and "android."

Welcome back to Other Android Dreams, my journey through the novels of Philip K Dick and also some other sci-fi/spec-fic related matters along the way. Today’s post is going to fall squarely within that “other” category.

It’s been a little while since my last post on here, what with being away or sick, working or else looking for work, putting out the odd medieval history episode, or just being weirdly busy with life, as one sometimes is. So before we move along to the next PKD novel, I thought I’d get back on the horse/bicycle/other-vehicle-that’s-probably-not-a-wagon with a post inspired by some recent (to me) reading: a late-May article and a Czech play from the 1920s. In keeping with the theme of this newsletter, both of them are all about the earliest androids, some fictional, some less so, and some much older than you might imagine.

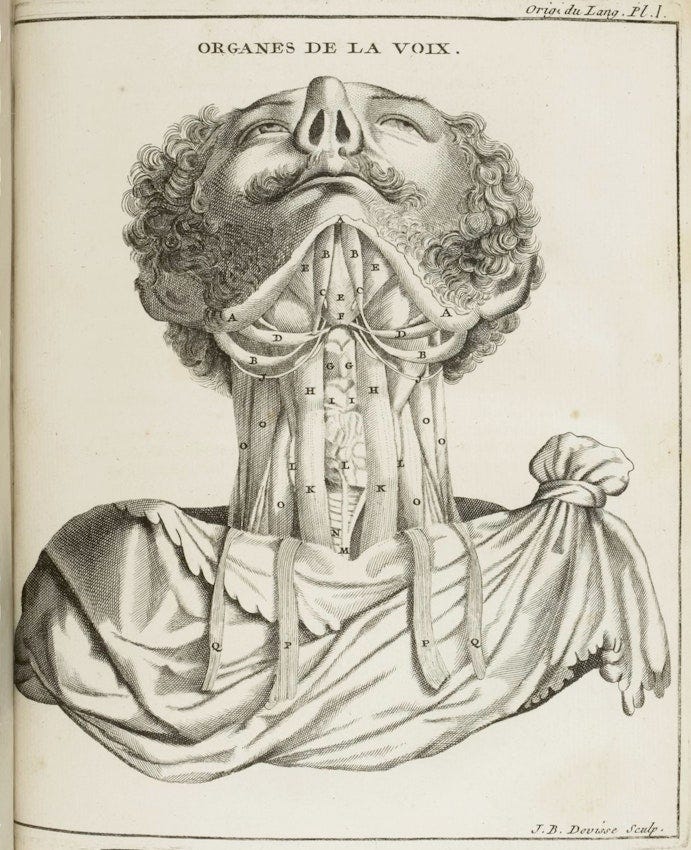

Appearing in Public Domain Review, the article in question is by Jessica Riskin, historian and author of The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument over What Makes Living Things Tick (which I haven’t read yet but does look fascinating). In that article, Riskin tells the story of the 18th and 19th-century quest to reproduce human speech, to fashion humanoid figures or heads that could mimic, as one 1738 observer put it, “what goes on in the larynx and glottis ... the action of the tongue, its folds, its movements, its varied and imperceptible rubbings, all the modifications of the jaw and the lips.”

It was, as you can see above, a lot. A lot to go about recreating with the materials then at hand. A lot to try to put into motion with 18th-century technology, and for some, it was simply too much. One scholar deemed the human voice “altogether outside the realm of imitation … [for] nature can use materials that are not at all at our disposal, and she knows how to use them in ways that we are not at all permitted to know.” But for others, it really didn’t go far enough.

In 1739, the surgeon Claude-Nicolas Le Cat enthused over the idea of an “automaton man in which one sees executed the principal functions of the animal economy,” everything up to and including “the secretions.” 15 years later, he was back on the topic, presenting his ambitious plans before a large audience. As someone in the crowd that day wrote, “Monsieur Le Cat told us of his plan for an artificial man... . His automaton will have respiration, circulation, quasi-digestion, secretion and chyle, heart, lungs, liver and bladder, and God forgive us, all that follows from it.”

The entire article is well worth a read, and not just for the various 18th-century talking heads. Not just for the fantastically named Monsieur Le Cat, the flute-playing faun, or even “The Defecating Duck,” as Riskin has elsewhere described that particular automaton. There are all sorts of little gems in there, and among them is the origin of the word “android.”

As Riskin writes, it all goes back to stories that spread about the 13th-century Dominican philosopher Albertus Magnus. Among his many more verifiable accomplishments, Albertus was said to have created a bronze man that was able to voice answers to all of his most troublesome questions and even, in an early example of AI doing your homework, to dictate some of his writings. Apparently the whole thing had come to an ugly end when his student, Thomas Aquinas, had finally snapped at all the incessant babbling and violently destroyed the bronze man.

Jumping forward about four centuries, we find the French king’s own physician, Gabriel Naudé, writing about Albertus and his purported bronze assistant. Naudé didn’t actually believe those stories, didn't think anything that lacked our muscles, lungs, and so on could possibly have approximated the human voice. He thought there probably had been an automaton, just not one that was actually conversational. But despite that disbelief, in a 1625 text he invented a new name for the 13th-century artificial human, and it was a name that would really stick, picked up in the 19th century to describe humanoid automatons and then by a parade of science fiction writers after that, our Philip K Dick included. Making use of Greek roots meaning “man-like” (and opening the door for a classic Radiohead song title), Naudé gave us the word “android.”

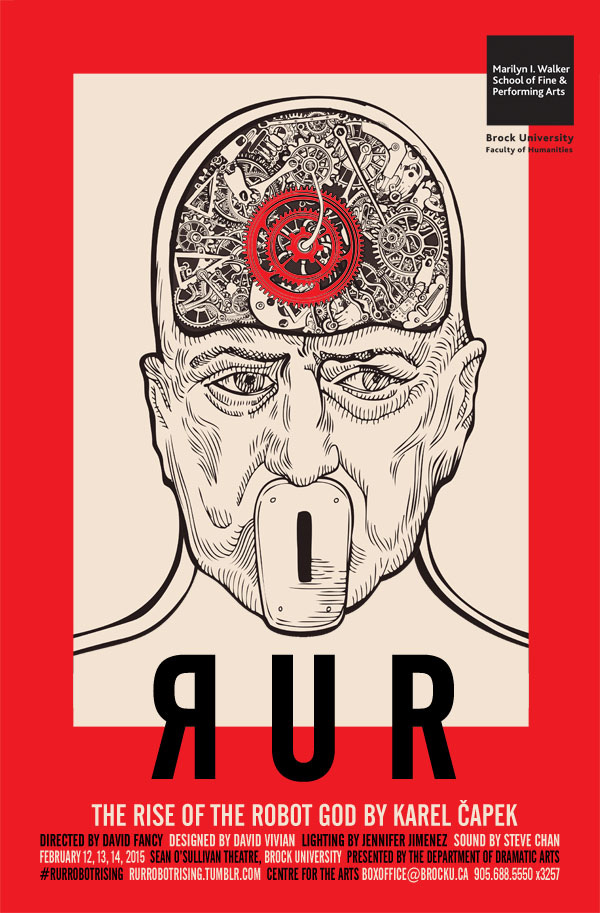

Reading about the android’s roots reminded me of another origin story that I came across earlier this year. Another first with persistent echoes in sci-fi, not to mention regular life, this one was in a drama written by the Czech playwright, novelist, and travel/gardening writer, Karel Čapek. First performed in 1921, the play was titled R.U.R., an abbreviation for Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti, or “Rossum's Universal Robots,” and in his use of the word “robot,” from a Czech word meaning servitude, or forced labour, Čapek was doing something entirely new. Automatons had been around for centuries, but there were no “robots” before Čapek, not by that name.

What Čapek had in mind was not quite like the mechanical arms or machines that now assemble so much of the material world around us. His robots were more like what Naudé would have called androids, imitations of human form, manner, and intelligence, and to an extent that would certainly have shocked and probably alarmed the 17th-century physician.

The robots of R.U.R. come in two varieties: at one end of the spectrum the crudely functional worker, and at the other something basically indistinguishable from a human, though lacking our full emotional spectrum. Some of Čapek’s characters view the promise of their robot-assisted future as a utopian one, freeing human life from poverty, suffering, and need. But as the play develops, we learn of workers’ revolts being cruelly put down by robot police forces, and of robots soon employed in escalating international warfare.

The direction all of this is headed is plainly predictable for a modern audience. After all, we’ve had the benefit of I, Robot, The Matrix, and The Terminator to prepare us, among so many other such stories. But it probably wasn’t quite so obvious in Čapek’s 1920s. Theatre-goers would have watched in horror as the robots turned against their human creators, entirely wiping them out but for one exception. Only a man named Alquist was spared, an employee at the facility where the robots were made and, unlike the others, a person who worked with his hands. A labourer, like the robots themselves.

The play ends on a surprisingly optimistic note given what’s come before, what with the end of humanity and all. The clock is ticking for the robots, whose lifespan is limited, and an aging Alquist, the only human on Earth, struggles and fails to discover the lost secret of creating new ones. Finally, with all looking bleak, he sees two of the robots together, Helena and Primus, and he is struck by their unique behaviour, the way they care for one another beyond even their own survival. With the play’s last lines, he addresses them as Adam and Eve, seemingly looking forward to a future for humanity of a kind, after all, with Helena and Primus carrying on like Noah after the flood. Everybody’s dead, but it seems like something will live on.

The two origin stories, that of the robot and the android, got me thinking about the way the two words are used today. Anecdotally, I feel like the development of something like actual androids has coincided with the term being abandoned, and just when it’s about to have its hour of glory too. “A.I. robot” seems to be the present language of choice, and maybe that’s because of the competing prominence of the brand name. After all, you don’t want your incredible new humanoid creation, the fulfillment of all of Monsieur Le Cat’s dreams, give or take a few bodily functions/fluids, getting confused with being just another phone.

Great article! I learned about R.U.R. a couple of years ago, when I had to read it / watch it as part of a university course I was taking. The play still holds up really well!

I never would have guessed that androids and robots had this long of a history! Thanks for sharing, Devon!